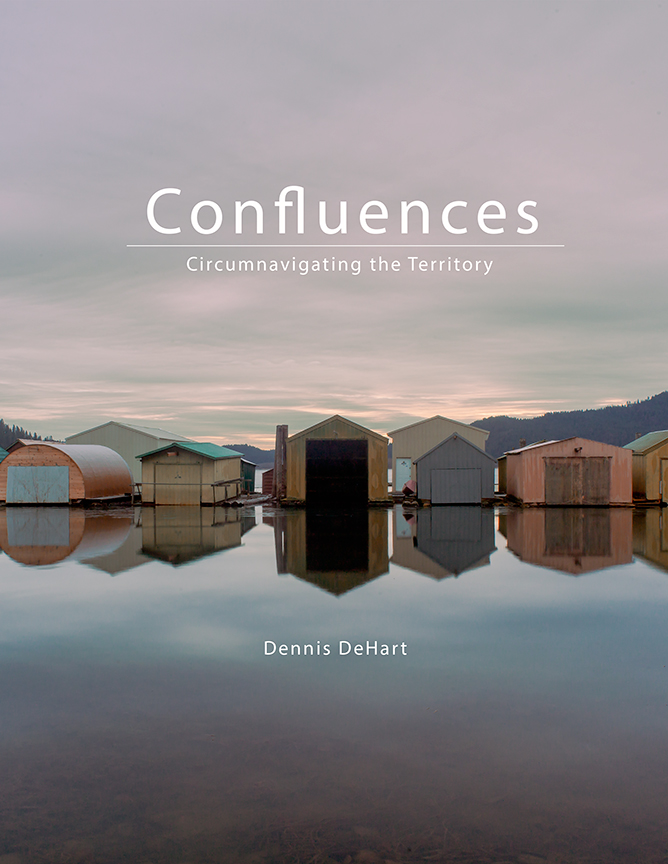

Confluences: Circumnavigating the Territory

Confluences is an interdisciplinary, lens based series of works focused on the Columbia River drainage basin. Spanning multiple US states and parts of Canada, the works engage with the interconnections of place, through the framework of rivers. Confluences is rooted in the tradition of art photography and contemporary social practice inquiry.

Included below is an excerpt of a longer Interview, by French Professor Heather Jane Bayly. The full interview was published in the French American Studies journal, as part of Aesthetics of Theory in the Modern Era and Beyond / Photographie documentaire, Transatlantica in 2015.

Confluences’ is based around the Columbia River and its tributaries. How have you tried to capture photographically the landscape and its cultural construction of this region?

The conceptual framework for ‘Confluences’ includes multiple moving parts. On the one hand, ‘Confluences’ is process oriented. I spend time traveling around the region, which includes biking, driving, and hiking. These trips enable me to look, wander, stumble, and innately revisit places. Many of the images I photograph stem from happening across places.

I often do research ahead of time and travel to locations with the intention of expanding the project. Working visually, I have the liberty of compressing, sequencing, and juxtapositioning time and space in creative ways. While many of my images are focused on landscape, I am interested in weaving together an expanded idea of place, which includes photographing built and natural spaces, in addition to creating portraits of people. The landscapes and portraits function together as characters in the broader story of ‘Confluences’. I am interested in generating analogies about place, which stems from a desire to emphasize links that might otherwise be played down or ignored. Barbara Marie Stafford’s book Visual Analogy: Consciousness as the Art of Connecting has been influential in my use of analogy as a non-linear way to communicate ideas and concepts visually.

Above: Four Installation Views, WSU Museum of Art, 2015.

You have said that you feel influenced by the ‘Myth of the West.’ Could you explain how it has helped shape your artistic vision of American landscape in ‘Confluences’?

‘The Myth of the West’ is the title of an exhibition that was held at the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, Washington in 1990. Chris Bruce, the current Director of Washington State University’s Art Museum, curated the exhibition. In the exhibition catalog, Bruce defines two major aspects of the visual arts in shaping and defining this myth which include: the “lone individual” who becomes a hero and “the landscape as the stage set upon which this drama of the western myth is played out.” Bruce, Chris, Henry Art Gallery, The Myth of the West, Rizzoli, 1990

I am interested in the representations associated with the American West. I recently read the book Photography Changes Everything, edited by Marvin Heiferman (2012). I was particularly interested in the essay by Edward Schupman, entitled “Photography Changes The Way Cultural Groups are Represented and Perceived”. Schupman is citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) nation of Oklahoma and produces educational material for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Native Americans. Some key points in Schupman’s essay include a discussion about the multiple face values of images and their importance as visual records. He also writes, “that by not reading photographs objectively, the images can easily tell as many lies as truths.” The essay includes several historical images of Native American’s, which over the course of history have take on many different kinds of readings ranging from overt racism to romanticized stereotypes.‘Confluences’ is simultaneously a celebration and critique of the “west.” The American west still holds powerful narratives within our popular imagination. For example, while visiting France in the spring of 2014, I observed French DJ David Guetta’s popular song and video called Shot Me Down. The music video is comprised of images depicting the American desert landscape and iconography (cowboys and cowgirls) including animated images drawn from Sergio Leone’s 1966 western, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. While the song and video are brilliantly complex, I found it curious how the songs visual vocabulary relied so heavily on an iconography drawn from American popular culture.

I am interested in creating a thoughtful narrative that avoids over simplifying complex issues and ideas about the west, and more specifically, the Pacific Northwest. I feel it is important to create contemporary images that are sensitive to issues of representation, while celebrating and acknowledging the richness of diversity and culture. In employing a multi-disciplinary approach, I am attempting to create a multifaceted vision of the west that simultaneously questions and illuminates varying aspects.

With the portraits in ‘Confluences’, I am resistant to staging my subjects. Generally, I talk with the individuals I photograph, ask for permission, and ease into making a picture. More often than not, the portraits are unsuccessful for numerous reasons including a lack of emotional and/or aesthetic complexity. What I am interested in with the portraits is a kind of collaborative in-between, in which the portrait is neither candid nor staged. I am looking for a kind of authenticity that is not colored by reinvention.

The full interview including an introduction by French Professor Heather Jane Bayly can be found in Transatlantica. http://transatlantica.revues.org/7213

Download a PDF of the interview: transatlantica-7213-2-interview-of-dennis-dehart-about-confluences

Confluences, Essay, Part 1. Published in Places: Design Observer, 4.13

This story begins with salmon eggs. In 2011, I was camping with my son Asher, then five years old, along the Selway River in North Central Idaho. He was playing on the riverbank when he reached into the water and pulled out a gelatinous mass of pinkish orbs. As he admired the orbs both in horror and awe, I noticed a battered salmon thrashing in the river. It’s going to attack my son, I thought, before realizing the ludicrousness of the idea. The salmon had just spawned and was preparing to die. In her final gesture, she had transferred her life to the eggs that were now in my son’s inquisitive hands. This experience left a profound impression on me. The salmon had traveled some 700 miles, through eight dams and four rivers, to return home and lay her eggs. In a simple gesture of curiosity, my son negated a portion of her efforts.

For my photographic series Confluences I have been circumventing the territory of the Inland Northwest, following the rivers as my guide, mapping a watershed I now call home. Confluences examines the multiple narratives inherent in place. The photographs engage with Native American history, land use, environment, energy, poverty, agriculture and industry in rural Eastern Washington and Oregon, and Northwest Idaho. Weaving together landscape, portrait, and still life, they express the unparalleled beauty and tragedy of the dynamic and complex landscape and its inhabitants.

Perhaps the region’s most significant confluence is the meeting of the Snake and Clearwater rivers at Lewiston, Idaho; 465 miles from the Pacific Ocean, Lewiston is the farthest inland seaport in the western United States. Seagoing vessels travel through numerous locks in order to deliver their goods. Downstream, they continue on the Columbia, once a powerful river, now a series of slack-water lakes behind large dams controlled by the central brain of the Bonneville Power Administration in Portland, Oregon.

The dams are either the life or death of the region, depending on whom you ask. Grand Coulee Dam is the largest electric power-producing facility in the United States and is a source of cheap energy for the Pacific Northwest. Grand Coulee is also a central component in the Columbia Basin Project, which irrigates 670,000 acres of once barren and now fertile farmland in Central Washington. On the inverse, native peoples have been displaced, the wild salmon population has been decimated, and the Columbia Basin Project is, in many respects, a financial sinkhole.

Confluences is my attempt to examine and reexamine a complex and layered series of interconnected places through the lens of the now. It is a messy affair in which history has allowed me the luxury of some objectivity, but the project would not make sense unless it came from the heart.

Semelparous: Remix. Single Channel HD Video, Continuous Loop, Total Running time: 5:10 minutes, 2015. A video art work of original and appropriated imagery created in conjunction with the project, Confluences, 2013-2016.